page 9 of 20

The Phenomenology of Tools

“We are eternally subjective: but there are objects.” Alfred Kazin.

The quill pen used to write the Declaration of Independence, we could all agree, would have greater historical significance than the pen then in service to the tenant across the hall. Never mind that these could have been identical instruments, pared to points only moments apart. They would remain forever distinct: the difference being the one’s habit of transferring genius to paper. This pen scratched a watershed moment in time, while the other likely toiled over newsy letters home. One would be like the pocket bible that stops a bullet: it could never be just a bible again. Meaning would well up around the obliterated language.

Having made the point for exceptional use, I should say that I’d also love to own that other pen, since I’d be better suited to it. Years of routine use will also leave their mark, as evidenced in the beat-up tools around me, in the beat-up me. Do old ambitions live in instruments, in projects, in places? Does the plan stay in your head, the echo in your hammer? And if so, how would you approach such tools, photographically?

Having made the point for exceptional use, I should say that I’d also love to own that other pen, since I’d be better suited to it. Years of routine use will also leave their mark, as evidenced in the beat-up tools around me, in the beat-up me. Do old ambitions live in instruments, in projects, in places? Does the plan stay in your head, the echo in your hammer? And if so, how would you approach such tools, photographically?

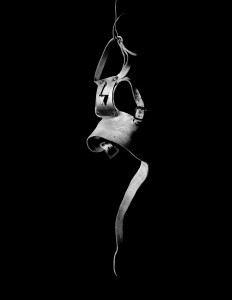

Head-on, I’d guess; certainly not in some gauzy set piece, where you prop them up on barn wood next to a kerosene lantern and a pair of leather work gloves. Nor should they be made Photoshop-cute, with brushed edges and patchy sharpness. Only a later generation could think that way. If you’ve ever earned a living with tools, were said to be a good hand, you know that you’ve also resented their dim silences and limiting scope, their habit of lowering your gaze. With items this personal, it’s better to lift them out of context and let them infer in space. Let them auger toward abstraction, which is surely where they’d go without us.

—

Here’s the hammer I swung in Arizona, working that mining company job on the Tohono O’Odham reservation and living with a buddy in Casa Grande. The rez is where we’d watch small clusters of Mexicans plod through Sonoran desert toward the irrigated fields up north. They wore two layers of clothing and carried almost nothing, luggage being a dead giveaway. We sometimes gave them water from our Igloo coolers, but no one said much or made sustained eye contact, including the natives and Latinos on the crew. This was in my trailer-house phase when, out of habit, I pined for a girl in Utah while reading the Beat writers, The Crack-Up, The Nick Adams Stories, Steinbeck’s letters, The Guns of August. It’s where I struggled with Absalom, Absalom! and quit on Ulysses. It’s where I fell in love with biography. Few things are as instructive as the full arc of a life. As for the hammer, I scratched employee number 1256 into its fiberglass handle on my first day. The number is barely visible now, and only when tipped into backlight. This hammer later delivered me to Denver, to Alliance Nebraska and Sioux Falls South Dakota. It helped build houses and barns and huge potato warehouses. It paid down my college loans and financed much of my trip around the world. It kept me in shape. Only I know where it’s been, or care.

Here’s the hammer I swung in Arizona, working that mining company job on the Tohono O’Odham reservation and living with a buddy in Casa Grande. The rez is where we’d watch small clusters of Mexicans plod through Sonoran desert toward the irrigated fields up north. They wore two layers of clothing and carried almost nothing, luggage being a dead giveaway. We sometimes gave them water from our Igloo coolers, but no one said much or made sustained eye contact, including the natives and Latinos on the crew. This was in my trailer-house phase when, out of habit, I pined for a girl in Utah while reading the Beat writers, The Crack-Up, The Nick Adams Stories, Steinbeck’s letters, The Guns of August. It’s where I struggled with Absalom, Absalom! and quit on Ulysses. It’s where I fell in love with biography. Few things are as instructive as the full arc of a life. As for the hammer, I scratched employee number 1256 into its fiberglass handle on my first day. The number is barely visible now, and only when tipped into backlight. This hammer later delivered me to Denver, to Alliance Nebraska and Sioux Falls South Dakota. It helped build houses and barns and huge potato warehouses. It paid down my college loans and financed much of my trip around the world. It kept me in shape. Only I know where it’s been, or care.

The point is: we seem to have it within our powers to imbue our things with meaning, simply by using them. We invest them with purpose and they reward us with definition. It’s an easy concept: think relics in altars, guns in museums, rings on fingers. We don’t even need to think about it. We can’t not do it. And the fewer tools we have, it seems to me, the more meaning they’re apt to absorb. I own several hundred tools, while my Dad got by with 25 or so, and that may be a stretch. I knew folks in town who lived abundant lives with five or six, astonishing as it seems.

There is separation in numbers: fewer tools are more iconic, more durable in memory, more receptive to ritual. The most useful tools are passed along and used more or less indifferently 75 and 100 years. “Been in the family,” we say, not really knowing how long. My son has my Grandpa’s pocket watch—a 1919 Elgin—while I have Grandpa’s saw and plane. There’s a rolling pin in our kitchen drawer rolling up the years; over 35 of them now. How many pies, you wonder, has it been intimate with?